Not So Soft Reboot Part One: Space: 1999

Shows like Falling Skies reboot themselves every year, and, perplexingly, sometimes during the season itself. Most of the time, as with Lost, and Revolution, and Jeremiah, the “soft reboot” of a sci-fi show between seasons is intended to address the problems of the first season, kowtow to the audience, and attempt to right a sinking ship. Every time, though, it goes wrong.

Lost’s storytelling is, at best, schizophrenic. This was expertly concealed by making the whole show into a time travel paradox.

Revolution correctly identified the problems and seemed ready to address them but, in recognizing and acknowledging the problem with the show’s general premise and nebulous Big Bad (sentient nanites with no clear motivation), the writers quickly found themselves painted into a corner.

Jeremiah put an end to the maudlin obsession with the past that haunted the first season and got down to world building, but then they decided that, to world build, they needed mysticism, religion, and a ridiculous Big Bad.

But those are the examples of halfway functional soft reboots. What about soft reboots that went horrifically wrong and, for years – or decades – have left us all scratching our heads? Oh, there are many… So I’ll just pick my favorites. First up, season two of Space:1999:

I’m not going out on a limb for this show because I’m not in accord with what you’re doing as a result…etc. I don’t think I even want to do the promos – I don’t want to push the show anymore as I have in the past. It’s not my idea of what the show should be. It’s embarrassing to me if I am not the star of it and in the way I feel it should be. This year should be more important to it not less important to it….I might as well work less hard in all of them.

–Scribbled note to showrunner Fred Freiberger by Martin Landau (Commander Koenig) in the margin of a Year Two shooting script

While many may call this a deeply flawed show from the get-go, I disagree. Season one was a thoughtful, wondrous voyage with just the right balance between adventure and cerebral sci-fi. The standard sci-fi tropes that, even by 1974, were eye-rollingly common, were all explored with a delicious little twist. When the crew turned into cave men, or aged rapidly, or woke up Satan, or became embroiled in a space ghost story, the audience felt then (and now) like it was fresh. The residents of Moonbase Alpha (or “Alphans”), were always fish out of water. They didn’t ask to be where they were, they weren’t equipped or trained to be where they were, and all they wanted was to make it through each day. The Alphans, mainly, were one, big dysfunctional family and so far out of their depth that you felt for them no matter how predictable the trope.

We open up the show with an already fractious crew manning Moonbase Alpha. While there’s a strong science contingent doing whatever it is future scientists do, these people were basically space janitors. Moonbase Alpha’s primary mission was to be a giant landfill for Earth’s atomic waste.

There’s a (quickly written out) illness that’s spreading through the base and the Earth government sends up an unlikable bureaucrat to figure out WTF and get shit up and running again. Commander Koenig’s mission is clearly intended to be a short-term thing. He’s sent up to be the axe-man for a bunch of corporate wonks, nothing more.

But an explosion in one of the atomic waste dumps sends the moon hurtling out of orbit on a one way trip into the void of space.

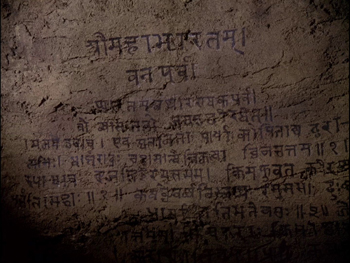

Throughout season one, the barely fleshed out series arc is that Moonbase Alpha is roughly following, in reverse, the same trajectory as Mankind’s progenitor race, and there’s some lightly made and never fully explored implications that the forefathers of Earth’s civilization were assholes. Pretty much every alien the Alphans meet seems to know of the human race, and a few even make direct reference to the passing of our ancestors. Season one ends on our progenitor planet, Arkadia, now a scarred wasteland. The away team struggle with an “older version of Sanskrit” that relates the last testament of the Arkadians. The big reveal in the episode is slow, measured, and all the more powerful for it. A great example of how season one’s pacing shined (unusual for the genre in the 70s):

ANNA: To you…who seek us out in the ages to come…we salute you. The desolation you find…distresses…no, grieves…we few who will soon die. Our civilization gone. Our world, Arkane or Arkadia, poisoned, dying. We who happened…ah, sorry, caused…our own…something…

VICTOR: Destruction.

ANNA: Yes…destruction. No need now to say…no, tell of that final…event? Happening?

HELENA: Holocaust?

ANNA: Yes, that fits…the final holocaust when our world flamed in the inferno of a thousand exploding suns. There’s more, but the imagery is difficult.

KOENIG: Keep trying.

ANNA: Arkadia is finished, but she, Arkadia, lives on in the bodies, hearts, the minds of the few who left before the end…taking…the life…the something…

LUKE: The seeds.

ANNA: The seeds of a new beginning. To seek out and…

VICTOR: Discover.

LUKE: No…begin. Yes, that’s it…to seek out and begin again in the distant regions of space. Heed now the teachings…testament…yes, the testament of Arkadia. There’s a passage here I can make no sense of. I’ll need the Reference Library. Then it continues. You who are guided here, make us fertile, help us…live again.

A beat.KOENIG: An Earth language. How could people from Earth be here twenty five thousand years ago?

LUKE: No. Earth people didn’t come here. The Arkadians…they found Earth. Ask Anna. She knows. Tell him, Anna. The trees. Tell him.”

ANNA: We found oak, pine, willow, beech…forty different varieties of trees all native to Earth.

LUKE: You heard the inscription. The Arkadians took the seeds with them. They found a new Arkadia. Earth. Our people originated here on this planet.

Season one was talky sci-fi. It was about discussing the sum of your parts and looking back on your decisions as the apocalypse inched ever closer. The Alphans were always at odds with each other and disrespectful of authority. They weren’t meant to be there and didn’t want to be there. This lends a certain darkness to Koenig’s occasional Jim Kirk moments. He’s not really in control, and every Red Shirt’s death is felt, elicits an emotional response, and occasionally shapes the choices made throughout the entire episode.

And then there’s season two…

The show’s soft reboot changed everything. The first thing you notice is the sets. We go from the window-lined “Main Mission” of season one, where cast members gazed out in wonder or horror at the alien worlds around them, to a more military-minded CIC deep within the base. The chattering computers and primarily scientific support team are gone, replaced, again, with a more military presence. The nominal first officer in season one was the chief scientist, Victor, played to perfection by the great Barry Morse. In season two, that role falls to a new character, Tony, the brash “chief of security” whose job is to be hot-headed and cause more trouble than he’s worth. The cast also gains their own Seven of Nine – the metamorph Maya, played by the sexy Catherine Schell. The fact that she’s mature, emotionally functional, and deeply involved with idiot Tony makes the forced father figure aspect of Koenig’s relationship with Maya downright weird.

Disconcertingly, most of the cast are gone. Victor – the show’s Mr. Spock – vanishes without a trace. The only nod, for the keen-eyed fan, is a population count at the start of the first episode that’s one short of what it was at the end of season one. That, however, doesn’t explain the disappearance of other season one regulars — Paul (who filled the brash brawler role Tony assumed), Kano (who repeated what the computer said), and Tanya (who made moon uniform stretch pants look amazing before Maya filled them out). Dr. Mathias, who was always a better doctor than Helena because she was so busy tagging along on every single away mission, gets only two episodes before he, too, vanishes without explanation.

Action becomes more vital than storytelling. In season two, the Alphans carve a path through the universe with a near homicidal shoot-first mentality. They’re better armed than before and willing to use the full force of their weapons even when they’re obviously in the wrong.

The dysfunctional family aspect is gone, replaced with a more structured feel. We’re no longer on the surface of the moon, full of wonder, terrified by aliens. Now we’re on a de facto starship bridge, with a de facto starship crew, working through storylines that better belong to the continuing voyages of starship XYZ. Where once they mourned life on Earth and accepted their fate, looking ahead into the unknown for a new home, now they’re weirdly obsessed with returning to Earth. In episode five, they actually use alien magic to fling themselves back to Earth…400 years too early. A few episodes later they fall prey to an alien who claims to be God and can deliver them to Earth (or, rather, create a new one), a two-part story towards the finale is all about how willing the Alphans are to accept anything from hostile aliens who present themselves as a rescue party from Earth.

Meanwhile, action abounds! There’s no Victor around to ruminate. Koenig brawls, Tony rushes ahead where angels fear to tread, Red Shirts die lonely, pointless, nameless deaths. The monster-of-the-week syndrome is sci-fi by the book. Maya tries to be a voice of reason, as she’s Victor’s spiritual replacement in season two, but her job is primarily to be the most ineffectual metamorph ever. Her transformations are usually into utterly useless creatures – birds, mice, monkeys, german shepherds – and she’s even more vulnerable in these forms than if she had just stayed a woman and shot the bad guys with a laser. In “The Rules of Luton,” Maya changes into a falcon and is captured. A rickety, handmade cage prevents her from transforming because she’ll be “crushed.” If she doesn’t transform back to human form within an hour (something often contradicted in the season) then she’ll die. The entire third act is a desperate race to free Maya from the cage.

So, look, Maya, I think if you go ahead and transform back into your 5 foot 7, 125 pound self, that cage made out of sticks and reeds won’t be an issue.

When not a mouse or a bird, Maya got to wear terrible gorilla suits.

Season two’s woes can be blamed on one man – Fred Freiberger. Space: 1999 was the brainchild of husband and wife team Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, but they split up and brought in Freiberger to revamp season two. He was hyper-critical of everything that had made the show great up to that point:

“They were doing the show as an English show, where there was no story, with the people standing around and talking. They had good concepts, they have wonderful characters, but they kept talking about the same thing and there was no plot development. … There was nobody you cared about in the show. Nobody at all. … In the first show I did, I stressed action as well as character development, along with strong story content, to prove that 1999 could stand up to the American concept of what an action-adventure show should be.”

But…the show wasn’t ever an action-adventure show!

Landau was bitter: “He had much less respect for actors and their input and contribution.” And Johnny Byrne, the season one writer who was the architect for the proto-seasonal arc where humanity was actually slowly heading towards their progenitor planet, hit the nail on the head: “But, suddenly, we were not talking about Earth people any more. We were talking about some kind of ghastly alternative Star Trekkers: they were Space Men; there was nothing they couldn’t handle; they could deal with anything that was thrown at them by aliens – who are inevitably malevolent. Their attitude was, “Get the bastards before they get us. Kick arse quick or they’ll kick us.” I told Freddie that he was going to lose the sense of wonder that we had had in the first series, and he told me not to worry because he was going to bring wonder into it, so we got a story called The Bringers Of Wonder, and that was Freddy. He completely changed the scripts that I had written, primarily to make it more like Star Trek.”

You might know Freiberger’s name. He’s the man who drove the final season of Star Trek into the ground, and manhandled the final season of The Six Million Dollar Man. After killing three well-loved sci-fi shows, he went on to completely fuck up the first attempt at a Westworld TV series, 1980’s Beyond Westworld.

We’ll end with a Friday LOL:

Next time: Battlestar Galactica